Outdoors

Leader of the Pack

In Greenspring Valley, the Maryland tradition of Foxhunting carries on. For huntsman Ashley Hubbard, it's all about the hounds.

Words by Lydia Woolever

Photography by Colin Marshall

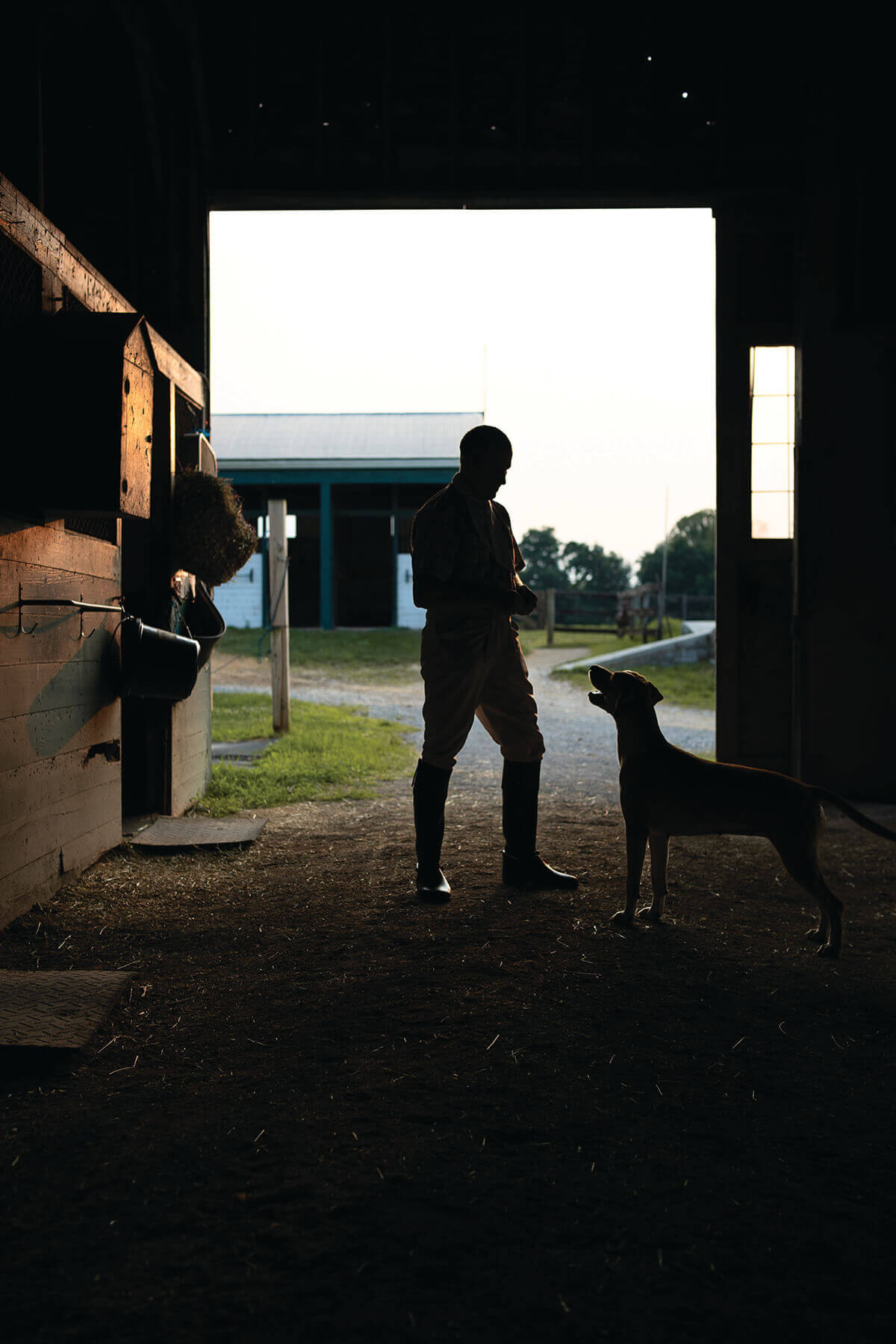

OPENING SPREAD: From left: huntsman Ashley Hubbard; the hounds on a summer morning stroll.

begins with a single hound—one long, lithe

male with a white and brown coat who leisurely

trots over the hill and down the driveway toward

Mantua Mill Road in Reisterstown. Then right

on his heels, the pack emerges, spilling over the

asphalt, sprawling out through the grass, rough-housing

along the horse pasture and field edges,

stopping to sniff the occasional trunk of an old

sycamore tree.

begins with a single hound—one long, lithe

male with a white and brown coat who leisurely

trots over the hill and down the driveway toward

Mantua Mill Road in Reisterstown. Then right

on his heels, the pack emerges, spilling over the

asphalt, sprawling out through the grass, rough-housing

along the horse pasture and field edges,

stopping to sniff the occasional trunk of an old

sycamore tree.

In the thick of them walks Ashley Hubbard, his pants tucked into tall boots and hands pressed tightly into his coat pockets, warding off the chill of this gray March morning. He moves quietly as the dogs fan out around him, ebbing and flowing in either direction but never straying far from his side. “Alright, Lancer! C’mon, Pilot!” he calls out to a few stragglers in a British accent, leading them across the road for a frolic among the daffodils of a neighbor’s meadow.

As the huntsman at Green Spring Valley Hounds, Hubbard oversees these 75 crossbred foxhounds. That includes Drama, Drastic, Risky, Ribbon, Poppy, Porter, Lattice, Legacy, Nasa, Nova, Novelty, and Notebook. He knows them all by name, by their black, brown, or blond spots, by the sound of their high yips, barky yaps, or bellowing howls.

After all, they spend most of their lives together. The 39-year-old father of two lives on-site with his wife and kids and has raised most of these hounds from the moment they were born, rising each morning with the first light to clean their kennels, feed them, get them exercised, and, three days a week, from Labor Day ’til April, gallivant them across Baltimore County during one of the 131-year-old club’s recurring foxhunts.

Blessing the hounds in Baltimore County, circa 1945. —Photography by A. Aubrey Bodine

“This is all I’ve ever wanted to do,” says Hubbard, who grew up in rural England and Wales, where his grandfather and stepfather were both huntsmen and a young Ashley spent every free minute helping with the hounds, ultimately following in his family’s footsteps at kennels from Canada to Maryland, where he’s worked for the past six-and-a-half years. “For me, it’s always been the norm. Start early. Work all day. It takes up your hours. And Christmas, Thanksgiving, you’re with the hounds. . . . It’s more than just a job. It’s every day of my life.”

In many ways, it’s that plain and simple, and yet complicated, too. Back in his native Britain, where the centuries-old sport began as a pastoral practice for farmers to protect livestock before evolving into an upper-class pastime, foxhunting has been banned for nearly two decades, with contentious debate still raging on today. Meanwhile in North America, where the sport arrived by way of the Eastern Shore in 1650, there are still more than 100 clubs. But here, hunters say they have increasingly focused on the thrill of chasing foxes, not killing them—“we took the dogs off and came home to dinner,” wrote George Washington after cornering one at Mount Vernon in 1785—though occasionally, this does happen, too.

Some also point to their horses or the scenery as reasons why they participate, but for Hubbard, it has always been about the hounds, and by 10:30 a.m., he’s loaded half the pack into a silver trailer and hauled them to a farm a few miles up the road. With the clouds parted, the mercury has climbed into the low 50s, and it almost feels like spring as 31 dogs excitedly tumble out into the corn stubble, prancing around a half-dozen trucks as club members saddle up their horses.

Before long, the entourage makes its way toward Piney Grove Road—male and female, most near retirement, decked in tweed jackets and velvet hats, their horses’ hooves clickclacking beneath them. Without much ado, they turn and trot down the country two-lane, then, with increasing speed, cut into the countryside, taking off down a winding valley, heading for a thicket of woods. Cars stop to watch. Neighbors come out of their houses. Even in the heart of Maryland horse country, it is a scene out of another place and time.

With Hubbard out front in bright-red regalia, he becomes the maestro, using simple commands or calls on his horn to cast the hounds in certain directions, while also following their lead and cues. It’s as if they share an unspoken language, known in the workingdog world as the “invisible thread,” which the huntsman says only comes with trust and time. Ultimately, the goal is for the pack to work as a team, picking up the fox’s scent and following it until the animal “goes to ground,” escaping into one of its burrows.

At this point, a few hounds will let out a low cry, “then I’ll get off the horse, make a fuss of them, and, depending on the day, we might go off and look for another,” says Hubbard, noting that hunts can yield several fox sightings, or sometimes none at all. “The fox runs circles around us every time. And that’s the thing: I respect the fox, too.” Around noon, one saunters across the train tracks near Old Hanover Road while the hounds searched a distant hillside.

A foxhunting scene in

the British countryside. —Wiki Commons

The wildlife knows no boundaries, but this bucolic terrain is a patchwork of private farms and residences, whose owners, several of them hunt members, give the club permission to traverse their land. Much of it has also been put into conservation easements to further limit development in this part of Baltimore County, and protecting habitat is a plus. Red fox populations remain robust throughout the region, according to the Department of Natural Resources, and more and more, the hounds are pursuing another common canine, the coyote.

By early afternoon, the hunters have chased two foxes and decided to call it quits. “It was a slow day,” says Cathy Jackson, 69, a retired photographer. “Other times, you just fly.” A bottle of bourbon is passed around and the hounds trail in slowly, having covered more than a dozen miles. “Piedmont is still out there, the stubborn old bugger,” says Hubbard, before the big hound trudges through the trees, earning a “good lad!” He brushes up to Sheila Brown, 70, one of the members who each spring temporarily fosters a pair of the pack’s brand-new puppies until their natural instincts kick in. “At some point, they put their nose to the ground,” she says, “and then it’s time to go.”

From there, they return to Hubbard. There will be no bubble baths or memory- foam beds, as is common in the lives of dogs these days, but the hounds don’t seem to mind. Back at home, they romp around their grass lot and pile on top of one another for an afternoon snooze. “They’re working hounds; they can be intense and focused,” says Hubbard, who points out the whimpers of those left behind on hunt days, “but they’re also big friendly goofs.” In fact, when a car pulls up the drive, they howl in a mighty chorus, wagging their tails ferociously and, if given the chance, dousing their visitors in a deluge of licks.

Months later, in the middle of August, their early-morning walks have evolved into off-season bike rides. The hounds shadow Hubbard and two other cyclists en route to a dip in the Western Run. A neighbor stops to see them and ask about the upcoming season, which won’t get underway in earnest again until late fall, when the local St. John’s Church formally blesses the hounds on Thanksgiving Day. One dog runs up to greet her, then another, and another, her clothes soon wet with slobber and paw prints, before they rush back into the stream.

“If you pet one, you have to pet them all,” cracks Hubbard, throwing out a few treats from his pockets before rallying the pack to head home. “Alright then, c’mon, you lot!”

And back down the road they go.

—Video by Lydia Woolever

Above: At Green Spring Valley

Hounds in rural Reisterstown, every morning

begins with exercise. After cleaning the kennels,

huntsman Ashley Hubbard leads the

pack down the driveway, past the horse pastures,

and along the winding country roads to

neighboring property, where they have been

given permission to roam their land. Hubbard

leads the way, a clear rapport and mutual

respect coursing between him and the dogs,

while his right-hand man, Brian Groves, holds

up the rear, making sure that all stragglers

are accounted for. Heading back in on this

March morning, the asphalt was covered in

dewy paw prints as the first spring flowers

poked through the dry grasses and a bevy of

songbirds could be heard in the nearby trees.

—Video by Lydia Woolever

Above: Whatever one’s views on foxhunting, there are few more magical sights in this pocket of Baltimore County than seeing

close to a hundred hounds follow their huntsman on summer mornings

as he bicycles to nearby water, like this pond outside of Butler. Over

further distances, the dogs get in shape for the upcoming hunt season

but also enjoy playtime. Hubbard carries treats for good behavior and

neighbors often come out to greet them, muddy wet coats and all.

Above: From the horse barn to

the dog kennels, hunt days are full of

excitement at Green Spring Valley.

Three mornings a week, Hubbard picks

out a few dozen hounds based on the

day’s terrain and the dog’s skill. The

chosen few eagerly scramble into a

silver trailer that will then head to a

meeting point on a neighboring property,

while those left behind often whine as

it goes, ultimately resigning themselves

to a midday nap. The hounds prefer

to be together as a pack, says Hubbard,

but each also has its own unique personality—some big and boisterous, others

small, shy, and sweet, but seemingly

all overjoyed by visitors, who they

enthusiastically sniff, lick, and lure

into ear scratches and hind-end rubs.