Travel & Outdoors

Greetings from Ocean City

A big, beachy love letter to going downy ocean.

By Lydia Woolever

ITY-DWELLERS KNOW WELL that by the end of May, when the mercury climbs toward the 90s, and the Mid-Atlantic air moves like molasses, there is one place, and one place only, to be in Maryland—and that is near the water. And for many generations of Marylanders, that has long meant heading out of the cities, over the Chesapeake Bay, across the Eastern Shore, until you see the white sands, washing surf, and whimsical wonderland of our state’s lone beach town. In fact, it’s hard to throw a baseball in Baltimore without hitting someone who’s spent time “downy oshun.”

Of course, getting to Ocean City is not always an easy feat. From Memorial through Labor Day, the typically two-and-a-half-hour drive takes twice as long, as this 10-mile barrier island—located on the easternmost edge of the Delmarva Peninsula, wedged between the Delaware line to the north, the Assateague Island National Seashore to the south, a trio of coastal bays to the west, and of course, to the east, the Atlantic Ocean—swells into our state’s second largest city. And yet weekend after weekend, well into September, road warriors from across the region will cram every chair, umbrella, bicycle, towel, and bathing suit that could possibly fit into their cars and brave the traffic to finally reach the beach. And many of the undeterred will tell you: “It’s worth it,” says Ocean City Mayor Richard Meehan, 75, a Towson native who spent childhood vacations in his now-adopted hometown. “There’s this feeling, coming over the Bay Bridge—like a sigh of relief. You just feel good about where you’re going.”

Which is to the sun and surf, of course. But also all the old motels, and the creaking boardwalk, and the blinking lights, and buzzing arcade games, and boundless shops, and bottomless feasts, generously dusted in salt and sugar. Over the past nearly 150 years, Ocean City has been a pandemonium of pleasure—offering all the fun, and nothing too fancy—where families flock for every form of leisure, and kids, by age or heart, can stay barefoot from morning to night. It often feels like time lingers somewhere between past and future here. As if, between the orange crush cocktails and Old Pro mini-golf courses and gaggles of seagulls soaring down to steal your Thrasher’s French fries, summer might just last forever.

“Sometimes I get out onto the beach early and look back to see the thousands of people standing outside or on their balconies, watching the sunrise over the Atlantic,” says Meehan. “It’s one of the most beautiful sights in the state of Maryland. And you can only see it in Ocean City.”

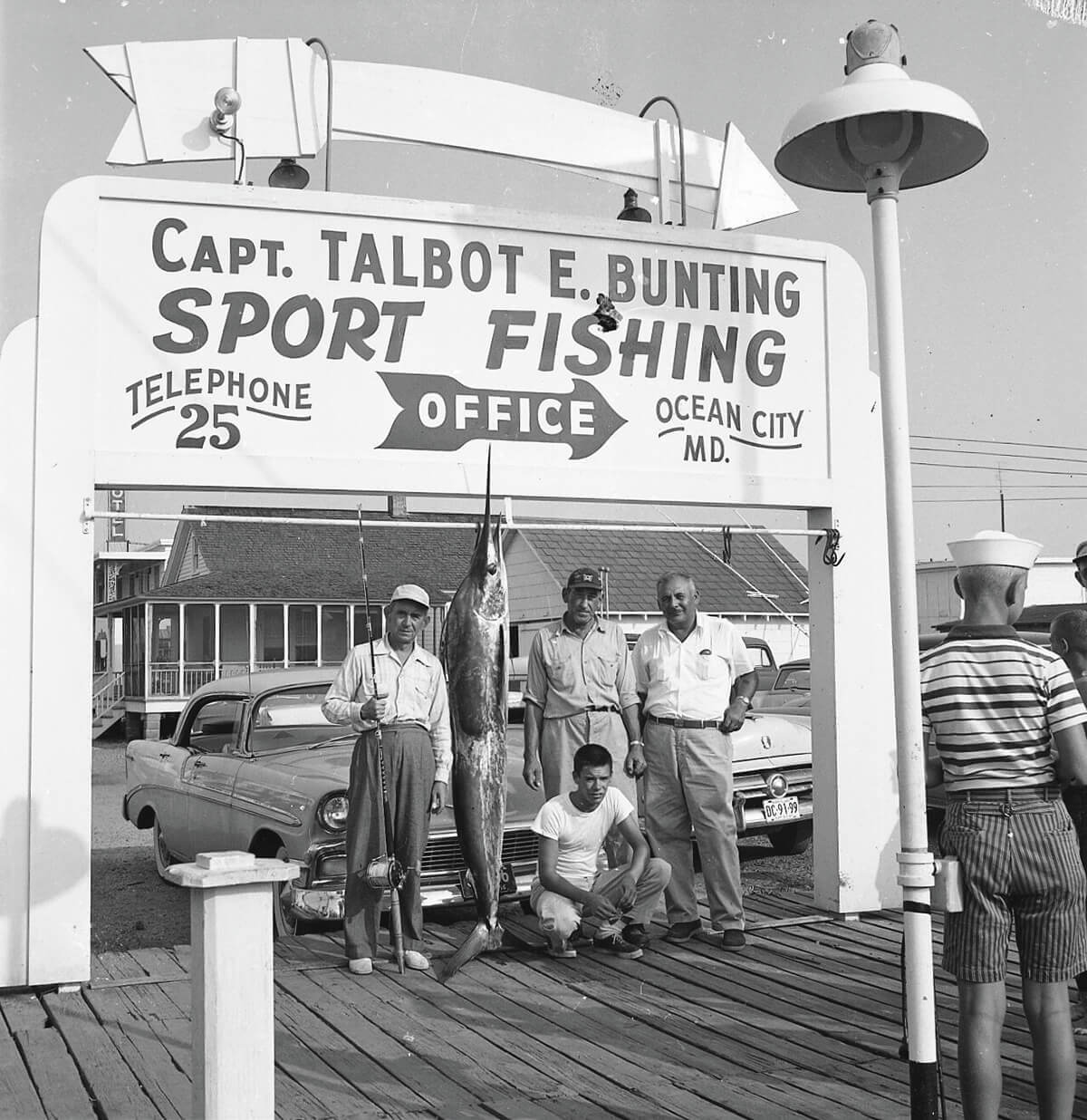

In a

series of retro scenes, a white marlin hangs

on the fishing pier and a visitors go for a

round on the rides in Ocean City. COURTESY NABB RESEARCH CENTER, SALISBURY UNIVERSITY.

LONG BEFORE THE BIKINIS, beach bars, and boardwalk, Ocean City began as little more than a remote fishing village, wedged between coastal bays and the Atlantic Ocean, first inhabited by the Native-American Nanticoke tribe, then settled by colonists on the easternmost edge of what would become Worcester County. It stayed this way until 1875, when the small town was founded with the opening of its first formal establishment, The Atlantic Hotel, advertised in the Sun as “large and commodious,” located “directly on the surf” with “splendid bathing,” for just $2.50 a night. At the peak of the Industrial Revolution, seaside strands had become popularized as a cure-all for the many maladies of urban life, and before long, entrepreneurs evolved these health-and-wellness retreats into a bona fide entertainment industry.

With no Chesapeake Bay Bridge, steamships would carry Baltimoreans to the Eastern Shore, from which they would train due east via the peninsula’s nascent railroad, to the newly dubbed Ocean City. In the early days, there was a post office, two general stores, and a few churches, but the boardwalk would take another quarter century. In 1900, it began with just five blocks, running between the town’s boundaries of North and South Division streets, covering what is now the island’s southernmost tip.

Walking this section of the resort town today, and you’ll come across a bevy of businesses that still stand from those early days, many of them run by descendants of their first- or second-generation immigrant founders, whose emporiums of rest, relaxation, recreation, or refreshments were some achievement of the American dream.

And down here, big changes were ushered in not just by man but Mother Nature. In August 1933, one infamous hurricane would dramatically alter the local landscape, ripping open a stretch of sand now known as “The Inlet” between the then-isolated Sinepuxent Bay and the sea, making way for a commercial fishing industry—one of the town’s early successes. (And in 1962, as the city crept northward, a notorious nor’easter would block any lingering lust to the south; the expansion of the downtown Baltimore Avenue across the Inlet into the proposed community of “Ocean Beach” was washed out with a three-day storm surge, after which the federal government protected that plot of land as the Assateague Island National Seashore.)

But even storms, stock market crashes, and world wars couldn’t contain the automobile age. The first span of the Bay Bridge was erected in 1952, and the rest was history. Streets were paved, town limited stretched toward Delaware, and within the next two decades, a bona fide construction boom was underway.

“I’ve witnessed several of the town’s incarnations,” wrote Raphael Alvarez, former Ocean City correspondent for the Sun, in Baltimore. “When I was a kid in the 1960s, mine was one of a half-dozen families—relatives and my father’s tugboat and crabbing buddies—who vacationed together each summer in Ocean City.” The Baltimore native swam in the ocean, and fileted fresh-caught fish, and watched the 1969 World Series, and made spin art on the Boardwalk, “blowing on it to dry.”

By the time of the second bridge span in 1973, the Ocean City we know today was beginning to take shape. Beaches were widened, bayside neighborhoods were built out of marsh, and The Carousel, owned by Lyndon Johnson political adviser Bobby Baker, had become the first hotel of “high rise row” north of 94th Street. Then part-time resident Gov. William Donald Schaefer sealed the deal with his “Reach the Beach” infrastructuve initiative in the late ’80s, transforming country two-lanes into coast-bound highways on the way to his own summer trailer—and his sleepy escape into a full-blown destination.

“What made Ocean City so special growing up?” poses Joe Kro-Art, 83, Baltimore native and owner of Ocean Gallery, a boardwalk institution since 1972. “That first moment of running down the beach, and seeing the Atlantic Ocean! The giant waves! Jumping in! Splashing around! Such excitement and fun! And, amazingly, it still is today.”

Retro beachgoers comb the

boardwalk.

IN THE DECADES SINCE, Ocean City has grown into the fullness of its grand name. Some 97 percent of the island has now been developed—with countless crab houses, candy stores, T-shirt shops, and surfboard shacks now stacked like dominoes down the main drag of Coastal Highway. The local population has quadrupled, and that’s not to mention the eight million visitors who swarm the seashore each year—from Baltimore, yes, but increasingly also Pennsylvania on up to New York, contributing more than $240 million to the local and state economy. Tourism is by and large the number one industry in Ocean City, “by a landslide,” says Amy Thompson, executive director of the Greater Ocean City Chamber of Commerce, with the “shoulder season” inching deeper and deeper into winter.

There are endless adages for how the off-season used to be. Fire a cannon down the boardwalk and you wouldn’t injure a single person. Roll a bowling ball down Coastal Highway and not a single car would be scratched. “On the Monday night of Labor Day, you used to look down Baltimore Avenue, and Ocean City was a ghost town until the next spring,” says Butch Arbin, 65, a Parkville native and head of the Ocean City Beach Patrol. “Nowadays, we’re a year-round resort.”

Of course, there are pros and cons of the town’s progress, as affordable housing becomes difficult to find, and the commercial sprawl oozes into once-quiet mainland communities like West Ocean City and Berlin. You can see it all across the Eastern Shore. On the backroads between Routes 50, 404, and 113, farm fields have succumbed to housing developments, strip malls, and a Royal Farms every other mile, or so it seems. Meanwhile, back in town, beloved landmarks bite the dust in town, and those classic cottages give way to upscale condominiums.

“I cried when they tore down the Sun and Surf movie theater,” says Meredith Moore, 40, an Ocean City native and owner of Innerbloom Floral on 30th Street. “It’s easy to be both sad that things are ending but also excited about the growth. Change is ultimately a good thing.”

A peak summer beach. COURTESY NABB RESEARCH CENTER, SALISBURY UNIVERSITY.

BUT NOW, AS IN THE PAST, enterprising businesses are rising to the occasion. Despite the town’s at-times Disneyland-like quality, many spots—even Sunsations and Seacrets—with many still run by local families, with some of the owners spending their childhood lunch breaks together on the amusement rides or over a slice of pizza. And a new wave of millennial Ocean Citians are returning home to open hip spaces like indie bookstores and farm-to- table restaurants, offering more inclusive and accessible options in this majority-white, predominantly middle-class community. Drive around and you’ll also recognize names like Ropewalk, Papi’s Tacos, and Pickle’s Pub, all from Baltimore—with the original owner of Shotti’s Point actually packing up and moving to the beach.

There is still Bike Week and the White Marlin Open, but also the Sunset, and Springfest, and Ocean’s Calling music festival, which will feature The Beach Boys this September. Sidewalks are being widened, bike lanes are being added, and the dune-strewn beaches are being repaired by the Army Corps of Engineers—which all happen to be free. Altogether, it’s getting harder and harder to dismiss the town simply as “Ocean Shitty”—a snub likely born out of its free-flowing Natural Lights and working-class clientele.

“There’s this feeling, coming over the Bay Bridge—like a sigh of relief...”

“Bethany and Rehoboth are beautiful, but Ocean City has always been more down-to-earth,” says Mickie Meinhardt, owner of The Buzzed Word bookstore on 119th Street, pointing to its affordability, with free beaches, cheap lodging, and family-friendly amusements. “You can come for Seacrets. You can come for senior week. But that’s not all this place is. . . . We’re a little beach town with a slower pace of life and salt-of-the-earth people.”

All to say, there might be no better time to take a trip, be it for the first time or the 50th. So go and see for yourself, using a few of the tips, tricks, and true stories that can be found below.

Because, believe it or not, those long, languid days of summer will be gone before we know it. Even in Ocean City.