[Editor’s note: On Oct. 28, the original date for the proposed deaccessioning, the BMA announced that it would pause the sale of the three works by Brice Marden, Clyfford Still, and Andy Warhol. In its statement, the museum noted that, while the original plan was discussed with AAMD leadership, “subsequent discussions and communications have made clear that we must pause our plans to have further, necessary conversations.” The BMA also reaffirmed its dedication to the goals of the proposed Endowment for the Future, saying “We have said change is important, but we have not taken the steps to enact it. The Endowment for the Future was developed to take action—right now, in this moment. Our vision and our goals have not changed. It will take us longer to achieve them, but we will do so through all means at our disposal.”]

In the wake of an announcement that the Baltimore Museum of Art plans to sell works by major artists Andy Warhol, Clyfford Still, and Brice Marden in order to fund a $65 million “Endowment for the Future,” objections have sprung up from all over the art world.

Though the endowment itself is well-intentioned—money would be used to care for the BMA’s collection, work toward equitable pay for its staff, create funds for diversity programs, establish evening hours, and extend free admission to special exhibitions—critics have raised concern over the museum’s method for raising funds.

The move comes after years of BMA efforts toward a more inclusive and progressive organization, with programs such as 2020 Vision and Necessity of Tomorrows working to highlight voices traditionally underrepresented in the often-homogenous museum world. A previous deaccessioning—the 2018 sale of several 20th-century works, including some by Warhol and Robert Rauschenberg—also raised some eyebrows. The proceeds from those sales went toward creating a “war chest” for acquiring new works by women and artists of color.

Op-eds condemning this new deaccession have appeared in The Art Newspaper and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications, and museum stakeholders have penned letters to the Maryland Attorney General and Secretary of State urging a cancellation of the sale and calling for an investigation into whether the plan is a breach of the public trust. One board member and former board chair, Stiles Colwill, has even resigned in protest of the decision.

But for those who aren’t familiar with the best practices governing the way art moves in and out of museums, the whole thing may seem a bit overblown. The museum wants money, the art is expensive, so where’s the harm in selling off three paintings out of nearly 100,000 for the sake of the bottom line?

It comes down to a few concerns, primarily with what is being deaccessioned, and how.

The BMA’s Interpretation of New Guidelines for Deaccessioning

Many critics have pointed out that the BMA’s announcement takes advantage of recent changes to the U.S. Association of Art Museum Directors’ (AAMD) typically strict rules pertaining to how proceeds from sales of artworks can be used. In April, the AAMD relaxed its guidelines for deaccessions in order to give museums some freedom to use such funds to prevent layoffs and closures as COVID-19 caused shutdowns across the country, allowing financial flexibility to “pay for expenses associated with the direct care of collections.” According to The Economist, the BMA joins The Brooklyn Museum, as well as other institutions in New York, New Jersey, California, Indiana, Massachusetts, and Texas in the decision to take the opportunity to auction off portions of their collections.

However, the BMA reports that it is not currently in dire financial trouble, and critics say the museum is taking advantage of the rule changes in order to generate funds for projects that do not necessarily fall under that umbrella. In his commentary for The Art Newspaper, Martin Gammon, author of Deaccessioning and Its Discontents: A Critical History, called the BMA’s decision to sell the three pieces “uniquely egregious,” writing that the museum’s rationalizations do not add up and must be challenged. Gammon contends that there is no significant curatorial reason that the pieces chosen for deaccessioning should be sold, and that it is clear the pieces were chosen based on their worth at auction to create a “windfall” for other operational purposes, including “shoring up salary disparities and other inequalities.”

In short, critics feel that using proceeds from the sale of works to increase salaries is at best a dubious manipulation of the new AAMD guidelines, and at worst presents a conflict of interest—as the museum’s curatorial team was asked to vote on a proposition that would directly affect how much they are paid. The Endowment for the Future would in part be used for salary maintenance and increases.

The Sale Could Be Detrimental to Both Artists and the BMA Collection

Concerns over the impact of losing these particular three pieces have also been raised. Minimalist painter Brice Marden’s 3 is the only painting by the artist at the BMA, and while defenders of the sale point to several works on paper as sufficient for the collection, others believe that the sale of the large oil on linen represents both a substantial loss for the public and a move that could damage the overall value of Marden’s work. As BmoreArt editor Cara Ober wrote in her analysis of the deaccessioning: “That Marden is a living artist also makes the sale more potentially damaging in setting a precedent, as it could impact the artist’s perception of value internationally and the museum’s credibility in collecting works by living artists.”

For many, Clyfford Still’s “1957-G” represents a significant loss. Still gifted the mid-century oil on canvas to the museum in 1969—the only time the Abstract Expressionist gave a single painting to a museum. Still worked in Carroll County for 19 years, and the gift is his only piece in the BMA collection. Some, Ober among them, have pointed out that this directly contradicts the museum’s efforts toward support for regional artists, as well as the wishes of Still himself.

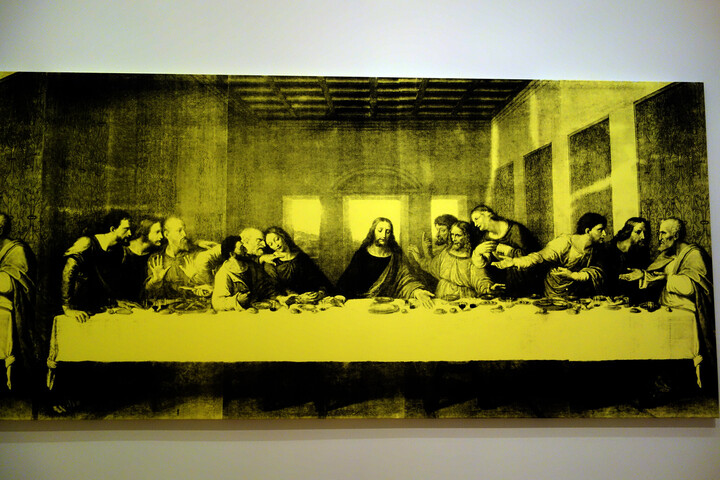

It is predicted that Andy Warhol’s “The Last Supper,” a highlight in the BMA’s contemporary Wing, will sell for around $40 million, not at public auction like the others, but through a private sale by Sotheby’s. The justification is that the painting is redundant to the collection, which features many other late-career Warhol paintings. But some have pointed out that the famous pop artist’s other paintings, including multiples from the Skulls, Ladies and Gentlemen, and Diamond Dust series, would present better options for sale. Instead of selling duplicates, the museum has opted to deaccession the piece from their Warhol holdings that would likely return the largest profit. Critics have also taken issue with the fact that The Last Supper is allegedly being sold for less than its potential value, and that the museum did not seek competitive bids from auction houses outside of Sotheby’s for the private sale. According to noted critic Christopher Knight’s Los Angeles Times commentary, the given price is $20 million less than what a comparable work sold for at Christie’s three years ago.

BMA Leaders Have Responded to Critics

The deaccession plan was pitched by BMA director Christopher Bedford, along with chief curator Asma Naeem and senior curator for research and programming Katy Siegel, all of whom have defended the proposed sale. In a response to critics in The Art Newspaper, Naeem and Siegel outlined their reasoning, as well as what they believe to be problems with Gammon’s and others’ critiques.

“Gammon frames the situation as a battle between timeless aesthetic values and opportunism. But what underlies his argument, and so many others like his, is a fundamental misunderstanding—or rejection—of the equity-based vision, values and considerations that undergird our decision,” they wrote. “…The BMA believes that the mission of the museum is civic, and that its dual responsibility is to create an internally equitable structure and an equitable and mutual relationship with the public, as expressed in the collection, exhibitions, programming and overall engagement.”

BMA Board Chair Clair Zamoiski Segal also released a statement defending the decision. In it, she pointed out that a supermajority of voting board members supported the deaccessioning and rebutted claims that their actions were a “dereliction of duty,” framing them instead as concrete steps toward long-term goals.

“The change brought about by the BMA’s Endowment for the Future will impact the shape of our collection, our ability to invite, accommodate, and connect with a greater swath of our community, and to honor the people who work at the BMA by paying them a fair and living wage,” she wrote. “These are not abstract goals; these are priorities with lasting impact and with which museums need to be engaged. This is an effort to live our mission, and the change is necessary and long, long overdue.”

What Comes Next

As things stand, the BMA plans to move forward with the October 28 deaccession, and the Maryland Attorney General’s office has not commented on whether or not it will investigate the allegations of breach of public trust.

It is more than likely that the three pieces will leave the BMA collection and fund the proposed initiatives. Paying all museum employees more equitably and allocating funds for acquisition of more diverse works are noble goals, and ones that would be welcomed in this moment when many cultural institutions are grappling with and working to address their historical shortcomings. Still, the concern is that this decision sets a dangerous precedent for how museums use their collections in the future. Museums are traditionally held up as institutions that work for the public good, in the best interest of those who benefit from their presence. The impression by some that these actions amount to cashing in chips in the commercial art market to free up funds for projects, not necessarily with value of the pieces to the public in mind, is the root of much of the outrage.

As Ober asked, “Once you sell one or two, what’s to stop you from selling more? And once you start selling more, especially in the name of paying your employees a decent salary or serving as a beacon for diversity and equity in an elitist, homogeneous art world, where do you draw the line?”

It’s a valid question, and one that, given the recent press and public outpouring, stakeholders and art admirers will likely keep a close eye on while the AAMD restrictions remain lax. Whether this deaccessioning ushers in welcome changes or further criticism will be up to the actions and accountability of the BMA.