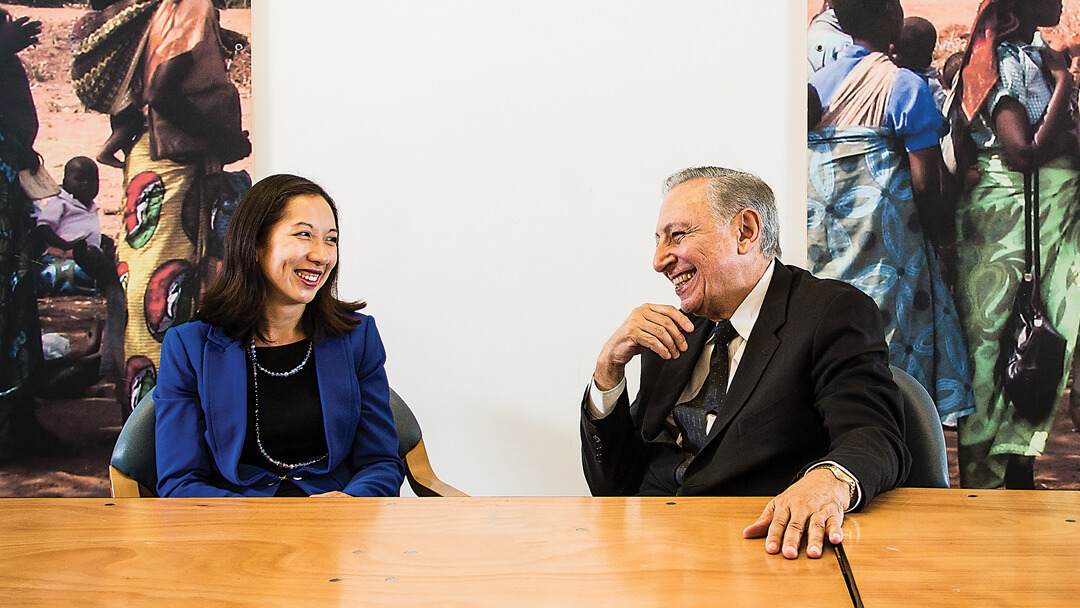

Dr. Leana Wen and Dr. Robert C. Gallo

The city health commissioner and the famous HIV/AIDS researcher discuss the toll of drug addiction, the future of AIDS, and making Baltimore healthier.

By Amy Mulvihill

Dr. Lena Wen and Dr. Robert C. Gallo at IHV in July.—Photography by Justin Tsucalas

I n 1984, virologist Dr. Robert C. Gallo co-discovered the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) as the cause of AIDS. He subsequently developed the first blood test for the virus and pioneered research into compounds that are used today in many AIDS therapies. Still full of mischief and curiosity at 78, he continues his research here in Baltimore at the Institute of Human Virology (IHV), which he co-founded in 1996. Though only 32, Dr. Leana Wen has already been a Harvard Medical School clinical fellow, an ER doctor, a consultant for the World Health Organization, and, as of January, Baltimore City’s Health Commissioner. Drs. Gallo and Wen sat down together for the first time at IHV. Wen started by explaining the scope of her role as health commissioner.

Leana Wen: One aspect of public health is ‘things that go wrong.’ My first week on the job, we had a suspected case of measles. It would have been the first in at least 10 years, so it would have been a huge deal. [Ed note: It turned out not to be measles.] Another aspect of it is restaurant inspections, animal control, and direct clinical care. We provide STD, HIV, TB services.

Robert C. Gallo: Wow. Jacqueline-of-all-trades! [The magazine] should just interview you!

LW: No, no! You discovered HIV! I do restaurant inspections! [Laughs]

RG: Long before I came here, when AIDS was the only [public health] topic, the press would ask, ‘What do you think is the most important topic?’ expecting me to say, ‘AIDS.’ But I would always say ‘drug addiction’ because it destroys families, creates criminality, breaks up neighborhoods, and also produces AIDS. I can’t think of anything more important.

LW: Yeah, actually, there’s a lot of synergy between us. HIV, that’s another big part of the work that we do. For Baltimore City, the disparities in HIV care and diagnosis are really profound. Eighty-five percent of those living with HIV are African-American. There are many populations that we know are hard-to-reach: men who have sex with men; African-American men who have sex with men; African-American men who have sex with men and work in the drug and sex trade. And we have multiple outreach efforts that are targeted to these specific communities. Examples are—

RG:

[Whispering to Nora Grannell, IHV’s director of public relations and marketing] She should be on our board.

[Turning to LW] You should be on our board.

LW: [Laughs] That’s okay.

RG: You don’t have to donate, don’t worry! It’s only two meetings a year!

LW: [Laughs] That’s extremely kind of you, but I think the mayor should represent the city. [ Ed note: Since IHV’s founding, every sitting mayor, including Stephanie Rawlings-Blake, has been on its board of advisers.]

RG: You’d get a lot of contacts, and it would be useful for us to hear you and to see what we can do in the city beyond [gestures to clinic]. Nora, make a note of it. She can’t refuse.

LW: This is the offer that I can’t refuse! I’m curious, if you project 20 years into the future, what is going to happen between now and then that is paradigm-changing?

RG: I expect that, 20 years from now, we won’t be talking about AIDS, but, then again, I don’t know for sure because it takes such a commitment. It takes the concentration of governments and the necessity to continue. PEPFAR [President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief] was an enormous contribution. It was created by President [George W.] Bush. We’ve been involved from day one. People believed that Nigeria and places like that would be impossible. It’s easier there than here. [In Africa,] they’re better able to follow up because they have less drug addiction problems; they have less family disturbance problems; they’re more authentically religious, wholesome.

LW: [Drug abuse] does tie into the fabric of everything we see in the city. There’s no issue that’s not touched by it. It ties into unemployment and crime. The numbers are totally shocking when it comes to access to treatment for mental health and substance abuse. Nationwide, only 11 percent of people with addiction are getting the help that they need. Would you say that only one out of 10 people with cancer can get chemotherapy? We would never find that to be acceptable. And yet, we find that acceptable for addiction. So that’s a big part of what we’re working on in the city.

“No, no! You discovered HIV! I do restaurant inspections!”

RG: Tremendous financial difficulty, though. I should answer something related to AIDS. So, everybody knows today that it could be ended. It’s been true since 1996. It’s a matter of money and governments coming together. There’s no new concept. We have the drugs to do it. Go out and find the people who are infected, keep the virus low, the epidemic is gone because you can’t transmit the low-level virus.

LW: What do you think about PrEP? [ Ed note: PrEP, or Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis, is a new preventative drug regimen, in which an individual at high risk of HIV exposure takes an anti-retroviral pill every day. With proper use, it has been shown to lower the risk of infection by up to 92 percent. ]

RG: I think treating so many zillions of people, and the cost, and being sure that they take the medicine, and we don’t get resistance [are] the problems on paper. But if you have the doctors available, and you make sure they take the medicine, it will work. So PrEP is a very positive thing. And in some high-risk communities, it’s going to make a tremendous change. So 20 years from now, with the right support, we could see a great diminishment in the epidemic, or its possible ending. And then you come to the issues that make headlines today: cure and vaccine. I think this is too much noise. I think we need to go out and find the infected people and get the epidemic down and focus on that. But all this research makes headlines if somebody gets a cure. But I don’t think anybody is anywhere near that. And vaccine: Within a month or two, we’ll be having an announcement here, from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, that our candidate vaccine starts Phase I.

LW: Wow. That is really exciting.

RG: It’s exciting, but we know that no candidate has solved the problem of the lack of persistence of antibodies. So that’s a scientific problem. So come back to me with the question: ‘So you don’t think the vaccine will be the great balm that solves the problem?’ Yes, I agree with you. It won’t be. But I think it will be a significant step, and we’re going to learn important things on it.

LW: I think it’s interesting that, from both of our perspectives, we’re seeing the entire spectrum of how we can resolve an issue like HIV. It would be ideal if we could come up with a vaccine, ideal if we could come up with a cure, but in the meantime, there are all these people who need to be treated.

RG: It’s not a science problem. The problem in Baltimore is a problem of education, drug addiction, poverty, the breakup of families, lack of information, and money. If you had enough money, enough dedicated people, you would stop the drug epidemic, stop family breakups or reduce them. You would have much less of a problem for Baltimore.

LW: I would agree. It’s difficult to have a city, any city, be healthy when you have that much concentrated poverty. Every single health issue is tied to poverty and economic opportunity in some way. Like cardiovascular disease: It’s the number one killer of men and women in the United States. I can tell my patients, ‘You should eat healthy and exercise.’ One in three African-Americans in the city lives in a food desert. They don’t have access to fresh groceries. They don’t have a car to go drive to Whole Foods. They can’t afford groceries at a place that sells healthy food. One in 12 white people lives in a food desert. Only one in 12 white people versus one in three African-Americans. That is why we have the health disparities that we do. You know, this whole ‘personal responsibility’ narrative only works if we’re able to level the playing field to give the same opportunity to everyone to live a healthy lifestyle.

RG: I published two or three editorials in The Washington Post calling for PEPFAR for cities of the United States. Do you remember the Marshall Plan? We did it for Europe after World War II. Don’t you think this is at the magnitude that we need a Marshall Plan? And where could the money come from? I said, ‘Why not use biodefense money?’ Because a virus is a ‘bio’ and [AIDS] is ‘terroristic’—and so is drug addiction.

LW: What if we could start with a pilot here in Baltimore, for $20 million? This is our proposal. We did actually publish an article in The Washington Post a couple months ago with this plan. For $20 million, we could get addiction and mental health treatment on demand. Specifically, have 24-7 treatment on demand; just like you have in the ER for physical health, you have an ER for mental health and substance addiction.

RG: Twenty million could solve it?

LW: Twenty million over three years.

RG: There’s a lot of money for biodefense. Twenty million of that money for you would be peanuts.

Drs. Gallo and Wen discuss the importance of success stories.

LW: One of the remarkable things that has been done in public health: Seven years ago, Baltimore had the fourth-worst infant-mortality rate in the country. And we were able to convene over 100 nonprofits, academic groups, and city agencies to come together under the umbrella for B’more for Healthy Babies that resulted in Baltimore having its lowest infant-mortality rate ever last year. And this year, we’re announcing a record low of sleep-related infant deaths, and a 32-percent decrease in teen birthrates.

RG: That’s a headline.

LW: Well, not a headline, but that’s why we do what we do.

RG: Well, it is. It is because positive news is really useful and greatly needed in the area, the city. And I think that’s very positive news, and it’s the kind of thing that often newspapers don’t say. It’s not going to be on the front page, but if you say infant-death mortality was skyrocketing, you’d have front-page news.

LW: We’d love to have good stories be told. Especially in the wake of the riots, there are so many bad stories being told in Baltimore, it’d be nice to see the things that we’ve done well.

-

Kwame Kwei-Armah & Lawrence Gilliard Jr.

-

Reverend Donté L. Hickman Sr. & David Warnock

-

David Simon & Laura Lippman

-

Denise Koch & Stan Stovall

-

Josh Charles & Derek Waters

-

José Antonio Bowen & Shanaysha Sauls

-

Laurie DeYoung & Konan

-

D. Watkins & Clarence M. Mitchell IV

-

Gaia & Doreen Bolger

-

Deb Tillett & John Davis

-

Damian Mosley & Linwood Dame

-

A Conversation with Dan Deacon

-

The Burning Question

-